The Non-fiction Feature

Also in this Monthly Bulletin:

The Memoir Spot: Smacked by Eilene Zimmerman

The Product Spot: Last Week Tonight – Harm Reduction episode

The Pithy Take & Who Benefits

Sam Quinones, a US journalist, carves a trail—from west to east, with black tar heroin, and from east to west, with OxyContin—of the beginnings of the opiate explosion. Black tar heroin sped across the country as people from a small town in Mexico engineered a remarkable delivery system focused on convenience and customer satisfaction. OxyContin streaked the other way as Purdue Pharma aggressively pushed a fabulously effective painkiller via aggressive marketing tactics, leading to pill mills and millions of unnecessary prescriptions. As black tar and OxyContin overlapped the country, the US, without realizing it, started drowning in addictions.

I think this book is for people who seek to understand: (1) how the Xalisco Boys so shrewdly marketed black tar heroin to middle- and upper-middle class white families; (2) why Purdue’s OxyContin became a blockbuster terror that tore through communities; and (3) how these two forces—black tar heroin and OxyContin—reveal the worst of capitalism and the best of government and community.

The Outline

The timeline

- “Opiate” describes drugs like morphine and heroin—derived directly from opium poppy.

- “Opioids” derive indirectly from opium poppy and resemble morphine.

- 1804: Morphine is distilled from opium for the first time.

- 1951: Arthur Sackler revolutionizes drug advertising.

- Early 1980s: Xalisco Boys establish heroin trafficking cells in Los Angeles.

- Early 1990s: Xalisco Boys expand in the US, their pizza-delivery-style system evolving.

- 1996: Purdue releases OxyContin, a timed-release oxycodone (a narcotic).

- Dr. David Procter’s Kentucky clinic is the nation’s first pill mill.

- 1998: “The Man” takes Xalisco black tar heroin east across the Mississippi River for the first time, and lands in Columbus, Ohio.

- 2008: Drug overdoses, mostly from opiates, surpass auto fatalities as the leading cause of accidental death in the US.

- 2014: Philip Seymour Hoffman dies, focusing attention on the opiate epidemic and the transition from pills to heroin.

New York, NY – 1951

- Arthur Sackler, an adman from a small marketing firm, met with the sales director of Charles Pfizer and Company, and Pfizer became his client.

- Pfizer had recently developed an antibiotic called Terramycin.

- Sackler sent salesmen to visit doctor’s offices in intensive drives to sell the antibiotic, which was a radical new concept. There were also direct mailings and other forms of advertising; all this led to $45 million in new sales in 1952.

- This marked the emergence of modern pharmaceutical advertising.

- Sackler also purchased the drug company Purdue Frederick.

Boston, MA – 1979

- Dr. Herschel Jick, from the Boston University School of Medicine, wondered how often patients in a hospital, given narcotic painkillers, grew addicted.

- He found that of almost 12,000 patients treated with opiates while in a hospital before 1979, and whose records were in the Boston database, only four became addicted. He didn’t make any claim beyond that.

- A graduate student named Jane Porter helped with his calculations and they sent their findings to the New England Journal of Medicine. It was titled, “Addition Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.” The journal published the findings.

South Shore, KY (near Portsmouth, OH) – 1979

- Dr. David Procter moved into town and built a clinic.

- Portsmouth is an industrial town in the rural heartland. It collapsed along with the rest of the American Rust Belt—a region unprepared for globalization and competition.

- The number of people applying for disability or workers’ compensation skyrocketed, and everyone needed a doctor’s diagnosis.

- Dr. Procter processed workers’ comp paperwork fast. And a new attitude took hold: The patient was always right, particularly when it came to pain.

- Dr. Procter prescribed opiates for neck, leg, lower back, and lower spine pain.

- He combined them with benzodiazepines (anxiety relievers, like Valium and Xanax). Opiates and benzos together led quickly to addiction.

- Soon, many in Portsmouth scammed prescriptions for pills and sold the pills for profit.

The Pain Revolution – late 1980s

- The World Health Organization claimed freedom from pain was a universal human right. If a patient said she was in pain, doctors should believe her and prescribe accordingly.

- The WHO deemed morphine an “essential drug” for cancer pain relief.

- Worldwide morphine consumption began to climb. The wealthiest countries, with 20% of the world’s population, consumed over 90% of the world’s morphine.

- The American Pain Society claimed that the risk of addiction to opiates was low.

- A culture of aggressive opiate use emerged by the mid-1990s, encouraged by pain specialists, medical school professors, drug companies, hospital lawyers, and others.

- It all revolved around the idea that painkillers were virtually non-addictive.

Enrique – a rancho in Nayarit, Mexico – 1980s

(A rancho is a swath of land dedicated to ranching)

- Enrique was living with a highly abusive father in a poor, rural area in Mexico.

- Teachers at his school treated children from the village’s upper barrio with respect, but were cruel to those like him who came without lunch. Some teachers forbade them from going to the bathroom until they wet themselves.

- His only thrill was that his mother’s brothers were in Los Angeles–a way out of his life. When he was 14, he took his birth certificate and boarded a bus to the US.

Denver, Colorado – 1990s

- The Denver drug world was changing. Officers began hearing about the Mexican state of Nayarit; the heroin in Denver, said officer Dennis Chavez, was all black tar.

- Chavez began tracking the Nayarit heroin connection, and he discovered that all the heroin in Denver came from one small town in Nayarit.

- What he had seen on the streets—dealers, couriers, drivers—looked random but it wasn’t. They were all from a town called Xalisco (ha-LEES-koh).

- Their success was based on a system for selling heroin retail.

- Think of it like pizza delivery. Each heroin cell of dealers had an owner in Xalisco who supplied the heroin.

- The owner communicated with the cell manager, who lived in Denver.

- A telephone operator took calls from people ordering dope.

- Drivers wove through the city, their mouths full of 25 to 30 little uninflated balloons of black tar.

- They had water bottles, so if cops pulled them over, they swallowed the balloons, which remained intact and were eliminated in waste.

- The operator told the addict where to meet the driver, they exchanged heroin and money, and the deal was done.

- Their business hours were 8am – 8pm.

- A cell could earn $5,000 a day in the beginning, and soon after that, $15,000 a day.

- The cell owner paid each driver a salary ($1,200 a week was the rate in Denver).

- Drivers were encouraged to offer deals: e.g., a free balloon on Sunday to an addict who buys Monday through Saturday.

- They competed with each other, but because they all knew each other from home, they were never violent. No guns, and none of the workers used the drug.

- Cell owners liked young drivers because they were less likely to steal.

- Cell profits were based on the markup inherent in retail.

- Desperate junkies usually can’t afford half a kilo of heroin. Almost no other trafficking group preferred to sell tiny quantities.

- With small quantities, prosecutors couldn’t get a good case. So, drivers who were arrested were usually deported.

- In a typical heroin supply chain, the drug moves from wholesalers through middlemen to street dealers. Every trafficker steps on it—expands the volume by diluting it—before selling. So, usually it’s 12% pure. But Xalisco black tar was 80% pure.

- Xalisco Boys were salaried, so they didn’t care about the potency.

- Cora Indians grew and harvested the poppies near Xalisco, and sold them to cell owners in Xalisco.

- A newly cooked kilo would head north in something like a boom box and, virtually uncut, it would hit the streets.

- Each tenth of a gram sold for about $15 and the cells grossed $150,000/kilo.

- It cost about $2,000 to produce a kilo in Nayarit, and in the US their overhead was cheap apartments, old cars, gas, and food, and $500/week/driver.

- Profit per kilo was well over $100,000.

- With flexibility on price, they could sell potent heroin cheaply, resulting in a decade-long rise in overdoses.

- They sold almost exclusively to white people—they figured out that wealthy white kids just wanted service and convenience.

- By the mid-1990s, the Xalisco Boys operated in a dozen major metro areas in the west.

Enrique – Canoga Park, California – 1990s

- Enrique discovered that his uncles sold black tar heroin.

- Enrique begged to work for them, and soon he had an apartment and two cars, and took orders for thousands of dollars of heroin a day. The apartment’s closets were filled with stolen Levi 501s, VCRs, and anything else addicts exchanged for dope.

Xalisco, Nayarit

- How did a small town of sugarcane farmers become the most proficient group of drug traffickers in the US?

- The first migrants from Xalisco settled in the San Fernando Valley and slowly started selling black tar heroin in parks in the early 1980s.

- In the 1990s, gang activity forced them to move their trade into cars, which gave them access to a broader client base.

- Soon they found new markets of thousands of middle-class white kids who began to dope up on prescription opiate painkillers.

- And, they found junkies who could navigate US methadone clinics.

- Methadone was seen as a treatment for heroin addiction, but soon methadone clinics became for-profit. Clinic owners also charged 20x to 30x what the drug actually cost, which was about $0.50 a dose.

- Maintaining large numbers of people on any kind of opiate, particularly on low doses, made them prey for someone with more potent drugs and faster delivery.

“Porter and Jick” – 1990s

- In time, Dr. Jick’s paragraph became known as “Porter and Jick,” and stood for the claim that less than 1% of patients treated with narcotics developed addictions.

- That statistic stuck, but a crucial point was lost: Dr. Jick’s database consisted of hospitalized patients from years when opiates were strictly controlled and given in tiny doses, all overseen by doctors.

- The paragraph actually supported a contrary claim: When used in hospitals for acute pain, and when tightly controlled, opiates rarely produce addiction.

OxyContin – Purdue Pharma – 1996

- OxyContin contains one drug: oxycodone, similar to Purdue’s prior MS Contin.

- Oxy contains large doses wrapped in a time-release formula that slowly sends the drug into the body, and has assuaged many people’s legitimate pain.

- To promote Oxy, Purdue hired Sackler’s firm (Sackler passed away in 1987).

- FDA approved Oxy in 1995 and allowed Purdue to claim that Oxy had a low potential for abuse because its timed-release formula would not result in steep highs and lows.

- No other Schedule II narcotic manufacturer received the FDA’s permission to make such a claim, and it became the cornerstone of Oxy marketing.

- Purdue positioned Oxy as the opiate of choice to be used for bad backs, knee pain, tooth extraction, headaches, sports injuries, etc.

- Purdue’s Oxy sales campaign was legendary, resonating with Sackler’s spirit and his focus on direct contact with physicians.

- Some Purdue salespeople, particularly in areas first afflicted with rampant Oxy addiction, made as much as $100,000 in bonuses during these years.

- Purdue also made continuing medical education part of its campaign. By the 1990s, CME had grown largely dependent on drug company funding. Companies shelled out millions to fly doctors to resorts and make pitches.

- Hospital lawyers told doctors that patients could sue them for not adequately treating pain if they didn’t prescribe these drugs.

- Oxy prescriptions rose from 670,000 in 1997 to 6.2 million in 2002.

- Oxy sales exceeded $1 billion in 2001 and 2002.

- The pill made up 90% of Purdue’s annual revenue.

Near Portsmouth, OH – 1997

- Dr. David Procter’s clinic was booming, with people (even from other states) parked along the street all day to see him for Oxy.

- Portsmouth was about to become ground zero of an explosion of opiate abuse.

- By spring 1998, Oxy addicts were everywhere, mostly young and white.

- It began with pill mills—starting with Dr. Procter—but the aggressive prescribing of opiates, particularly Oxy, expanded it further.

- A pill mill was a pain management clinic staffed by a doctor.

- If heroin was perfect for drug traffickers, Oxy was ideal for pill mill doctors.

- First, it was pharmaceutically produced with a legal medical use;

- Second, it created addicts, so people needed it everyday, they paid cash, and never missed an appointment.

- After Dr. Procter was injured in a car accident in 1998, he stopped seeing patients but kept the clinic open. He hired 15 doctors who had histories of drug use, previously suspended licenses, and mental problems.

- The DEA eventually caught on, and Dr. Procter pleaded guilty to conspiring to distribute prescription medication. He served 11 years in prison.

The Man – Columbus, OH – 1998

- The Man ignited the second wave of Xalisco heroin expansion in the late 1990s.

- In Reno, NV, he met someone from Columbus, OH who loved black tar heroin. He suggested that the Man should take it to Columbus, OH.

- Columbus had lots of white people, with large suburbs and highways, and was close to four states.

- When the Man arrived in 1998, it was likely the first time black tar heroin made an appearance east of the Mississippi River.

- Columbus was a pill town because pills were easier to trust than diluted heroin, but soon black tar exploded and found its way to suburban kids.

- The Man expanded to Wheeling, WV and met a woman who wanted to trade Oxy for black tar. Oxy, she told him, contained a pharmaceutical opiate, similar to heroin.

- His black tar, once it came to an area where Oxy had already tenderized the terrain, was sold to everyone—the transition from Oxy to heroin was easy.

- Oxy addicts sucked on and dissolved the timed-release coating to get to 40mg or 80mg of pure oxycodone.

- Addicts crushed the pills and snorted. As their tolerance built, they used more.

- Then they liquefied and injected it, while tolerance kept climbing.

- Oxy sold on the street for a dollar a milligram and people used well over 100mg a day. As they reached their financial limits, they switched to black tar.

- Black tar was potent, cheaper, and was easier to acquire.

- The Man realized that every Oxy addict was a tar junkie in the waiting.

- He expanded to towns like Columbus: wealthy places with growing numbers of addicts and no competition.

Los Angeles, CA – 2000

- The DEA and FBI arrested 182 people in a dozen cities in Operation Tar Pit, and it remains the largest joint DEA and FBI case.

- Enrique was arrested, too, and spent 13 years in prison.

- The Man was later arrested and sent to prison as well.

- However, they were all soon replaced by new Xalisco boys.

The Pain Revolution, completed – 2000

- The US consumed 83% of the world’s oxycodone and 99% of the world’s hydrocodone (the opiate in Vicodin and Lortab).

- Drugs containing hydrocodone became the most prescribed drugs in the US (136 million prescriptions a year).

- Between 2002 and 2011, 25 million Americans used prescription pills nonmedically. The pain-pill abuser’s average age was 22.

- For a long time, people who abused small-dose painkillers didn’t progress beyond that, and they rarely died from them. But Oxy was much stronger, and often served as an addict’s bridge between milder opiates and heroin.

Virginia – 2001

- John Brownlee became US Attorney for the Western District of Virginia.

- He saw people dying of Oxy all over the region, and subpoenaed all Purdue’s records related to marketing Oxy.

- The records showed how Purdue trained salespeople to market Oxy as if it were nonaddictive and didn’t provoke withdrawal symptoms.

- In 2006, Brownlee prepared to file a case of criminal misbranding against Purdue.

Columbus, OH – 2003

- Dr. Peter Rogers was at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in the adolescent medicine department and had never seen a teenager addicted to heroin.

- One night, a teenage girl (from a wealthy suburb) came in with her parents and she had diarrhea, pains throughout her body, and was hooked on heroin.

- Once he admitted her, word spread that you could go to Children’s and get detoxed. Dr. Rogers watched the new opiate epidemic emerge—hundreds of kids, all white and from well-to-do homes. All started with pills.

Portsmouth, OH – early 2000s

- Scioto County, OH had the most pain clinics per capita, and it became the pill mill capital.

- Although the pill mills were eventually shut down, in their last year of operation, 9.7 million pills were prescribed in Scioto County (population of 80,000).

- One key to the pill mill explosion was hiring from locum tenens lists: doctors seeking employment who had license problems, were alcoholics, etc.

By the 2000s, Xalisco ranchero farm boys, from a town of just 45,000 people, had become the most prolific single group of heroin traffickers in the US, supplying black tar in at least 17 states.

Virginia – 2006

- U.S. Attorney John Brownlee continued to investigate Purdue.

- Despite its ad claims, Purdue provided no study to the FDA to support the claim that it was less addictive.

- Purdue had falsified evidence to show a steady level of oxycodone in blood plasma, but the true graph shows an incredible spike and an incredible drop.

- Purdue supervisors taught salespeople to tell doctors that patients using up to 60mg of Oxy could stop without withdrawal symptoms.

- But, investigators found that company officials knew of a study that demonstrated the opposite.

- Brownlee filed criminal charges against Purdue, and they had a deadline to accept a plea agreement: one felony count of false branding.

- Michael Elston—who worked in the US Department of Justice while Alberto Gonzales was Attorney General for President Bush—called Brownlee.

- Elston asked Brownlee to postpone the plea, and said he was calling on behalf of a superior, who had received a call from Purdue, asking for more time.

- Brownlee ignored this and moved forward. One week later, his name showed up on a list of federal prosecutors recommended to be fired. Elston compiled the list.

- Purdue pleaded guilty to a felony count of misbranding Oxy; to avoid federal prison for its executives, Purdue paid a $634.5 million fine.

- Three Purdue executives pled guilty to a single misdemeanor of misbranding, and were on probation and had to do community service.

Ohio – 2007

- Ed Socie was an epidemiologist with Ohio’s Department of Health. In 2005, he noticed that poisoning deaths were climbing and realized that they were drug overdoses.

- In 2007, he and his supervisor discovered that 95% of all poisoning deaths were drug overdoses, in large part because of prescription pills.

- That year, drug overdose deaths surpassed auto crashes as Ohio’s top cause of injury death.

- In 2008, drug overdoses passed fatal vehicle accidents nationwide for the first time, following Ohio’s lead.

Nashville, TN – 2000s

- Judge Seth Norman runs the only drug court in the US that’s physically attached to a residential treatment center.

- These centers could keep most addicts out of prison, saving the state $32,000 a year.

- Most TN legislators viewed drug treatment as weak do-gooderism and stuck to the lock-’em-up attitude that their voters preferred.

- But, Judge Norman believed that this attitude had softened.

- Most of the new addicts were from the white middle and upper-middle classes and the white rural heartland—people who vote for, donate to, live near, and do business with the majority of TN legislators.

- Republicans across the country seemed to be changing their views on drugs. In Texas, Georgia, and other states, they encouraged a more forgiving set of laws.

- Many voters no longer pushed the “tough on crime” narrative now that it was their kids who were involved.

- Quinones observes that it felt like a moment of Christian forgiveness, but it was also a forgiveness that many didn’t grant to urban crack users.

Other than addicts and traffickers, most of the people Quinones spoke with were government workers. There has been a demonization of government and an exaltation of the free market over the previous thirty years. This story, though, focuses on the battle against the free market’s worst effects, taken on mostly by anonymous public employees.

Families

- Addicts, adults or not, often returned to live with their parents once they lost their jobs and houses. Parents lived in torment, watching helplessly as their kids fell apart.

- As addiction consumed white middle-class children, parents hid the truth.

- There were many athlete-addicts. Their parents were surgeons, developers, lawyers and had everything, yet sports seemed as much a narcotic, and drugs like Vicodin and Percocet provided coaches with the ultimate tool to get injured kids playing.

- Many parents once thought addiction a moral failing, and now understood it as a physical affliction. They thought rehab would help, but then realized that relapse was inevitable; it takes something like two years of treatment and abstinence, followed by a lifetime of 12-step meetings, for recovery.

- Additionally, insurance companies don’t want to fund addiction treatment with enough duration and intensity because society doesn’t demand it.

Philip Seymour Hoffman – 2014

- Hoffman was found dead in his apartment with heroin and a syringe in his arm.

- Within days, the media discovered that thousands of people were dying, and almost all the new heroin addicts were first hooked on prescription painkillers.

- Soon after, the pharmaceutical industry’s sales force arms race ended. Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, and others laid off thousands.

- Pfizer paid more than $3 billion in fines and legal penalties. This was less than three weeks of their sales.

People spent decades destroying community in the US, pulling apart the architecture of government that provided public assets—the things that made communal public life possible—that everyone took for granted. People simultaneously exalted the private sector and placed the free market on a pedestal; thus, the private sector developed a sense of welfare entitlement.

With opiates, the private sector has swiped the profits and the public sector has scrambled to cope with the collateral damage. The Sackler family, thanks to Oxy sales, has an estimated net worth of $14 billion.

How we move forward

- Keeping kids sheltered and cloistered in their rooms is connected to the idea that pain and emotional anguish are things to be avoided at all costs.

- The US pretended that the accumulation of things caused happiness, and built isolation into the suburbs and declared it prosperity. Yet, heroin thrives in isolation.

- The antidote to heroin is community. To keep kids off heroin and other addictive drugs, make sure they engage with people in the neighborhood and community—do things together, in public, often. And show kids that pain is part of life and is often endurable.

And More, Including:

- A brief history of the opium poppy, heroin, and methadone

- The import of Jaymie Mai and Gary Franklin’s research (state of Washington employees), which was the first time anyone in the US documented the deaths associated with the new prescribing of opiates for noncancer pain

- How Oxy turned pillscamming into big business for Portsmouth, and the crucial importance of the Medicaid card in aiding poorer people in getting Oxy

- Portland’s Lens Bias strategy to combat the Xalisco Boys

- Story after story of addicts and parents of addicts who want people to know that this could happen to them

- How the University of Akron’s athletics disintegrated under the pressure to win and the weight of pills

- How Philip Prior sounded the alarm about the excessive prescribing of Oxy as a gateway to heroin

- Ohio House Bill 93 in 2011, which regulated pain clinics and essentially closed pill mills

- Drs. Katheleen Foley and Russell Portenoy and their role in widely encouraging prescribing painkillers for patients

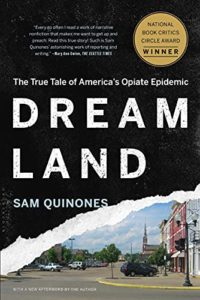

Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic

Author: Sam Quinones

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Pages: 400 | 2016

Purchase

[If you purchase anything from Bookshop via this link, I get a small percentage at no cost to you.]