The Non-fiction Feature

Also in this Weekly Bulletin:

The Fiction Spot: The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

The Product Spot: Winix Air Purifier

The Pithy Take & Who Benefits

150 years ago, bacteria, unknown and unopposed, laid waste to wounds and turned surgeries into horrifying, life-threatening experiences. Lindsey Fitzharris, whose Oxford PhD is in the history of science and medicine, describes in gory detail surgeons who didn’t clean their hands or instruments as they operated from one patient to the other, and hospitals that were rank with filth and miserable stenches.

Joseph Lister, armed with curiosity and a microscope, entered this realm determined to discover what caused infection. It is not an exaggeration to say that many of us owe our lives to him. I think this book is for people who seek to understand: (1) medicine in a world that was helplessly unaware of bacteria and germs; (2) the remarkable obstacles Lister overcame to discover and preach the dangers of bacteria and germs; and (3) how his relentless experiments altered not only the medical and surgical communities of the time, but also how hospitals and society regard cleanliness today.

The Outline

The Preliminaries

- Over the 19th century, London’s population erupted from 1 million to over 6 million.

- Single rooms could contain 30 or more people, all clad in soiled rags.

- Death was frequent; churchyards bursting with rotting corpses posed a huge public health threat.

- London streets were open sewers, releasing deadly amounts of methane.

- During this time, surgery was filthy.

- Surgeons wore bloody aprons and rarely washed their hands or instruments.

- Surgeons believed pus was part of the healing process rather than a sign of sepsis; postoperative infections caused most surgical deaths.

- No one knew how infectious diseases were transmitted.

- The threat of infection restricted surgical capabilities. Entering the abdomen or chest was fatal, so surgeons dealt with the external: lacerations, fractures, skin ulcers, burns.

Joseph Lister – childhood

- Born on April 5, 1827 to Joseph Jackson Lister (owner of a wine business) and Isabella Lister, two devout Quakers.

- Lister, thanks to his father, was fascinated with the microscope. They were usually sold as gentlemen’s toys, but his father made great use of it and corrected many of its defects (poor lenses, etc.).

- When he was older, he announced that he wanted to be a surgeon—this surprised his family, as it was a stigmatized job of manual labor and relative poverty.

University College London – 1844

- Lister began medical school, where students often lived next door to the bodies they dissected.

- Students didn’t wear gloves or other protective gear inside the dissection room.

- They were warned about the fatal effects of a slight crack in the skin.

- Mortality rates among medical students were high. Between 1843 and 1859, 41 young men, before ever becoming doctors, died after contracting infections at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Hospitals were overcrowded and grimy—breeding grounds for infection. In 1825, visitors to St. George’s Hospital discovered mushrooms and maggots thriving in a patient’s sheets. Surgeons were unconcerned with the causes of diseases, choosing instead to focus on treatment.

- Lister carried his microscope with him everywhere. Many believed the microscope was superfluous and its use wouldn’t lead to anything worthwhile.

- In 1851, Lister was at the hospital when a policeman arrived; he was holding Julia Sullivan, a mother of 8, who was stabbed by her abusive husband.

- Much of her intestines had slipped out; Lister slid them back through the stab wound and sewed the wound using a single thread.

- His decision to suture her was extremely controversial because an organ was punctured, but he was successful where many were not.

- Julia recovered well and her case was twice referred to the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, which stressed the importance of Lister’s suturing.

- Much of her intestines had slipped out; Lister slid them back through the stab wound and sewed the wound using a single thread.

- Lister encountered many injuries caused by poor living and working conditions.

- He also observed the effects of diet: people consumed large amounts of beer and meat, but almost no vegetables or fruit—many had scurvy.

In general, a sick person had a ¼ chance of entering a city hospital. Almost all London hospitals controlled inpatient admissions through ticketing. A person could get a ticket from a special hospital subscriber, who had paid a fee in exchange for the right to recommend patients to the hospital. Getting a ticket required tireless soliciting; people begged their way into the hospitals.

- Lister often conducted his own experiments and made his first major scientific contribution using the microscope to examine a portion of a fresh blue iris.

- He found that the iris was composed of smooth muscle fibers arranged in both constrictors and dilators, and that their actions were involuntary.

- Once, before an amputation operation, Lister cleaned the patient’s wound and washed her arm with soap and water. The amputation was successful and the stump healed perfectly; Lister attributed this to his sanitation efforts.

- Why was it that a majority of the ulcers healed when they were cleaned with a caustic solution? Lister thought that something in the wound itself had to be at fault.

- He began to use his microscope to examine pus scraped from infected wounds.

- He made a sketch of some entities that he thought might be parasites. He began to conduct broader investigations into the causes of hospital infection.

University of Edinburgh, Scotland – 1854

- Lister travelled to Edinburgh to study with a renowned professor of clinical surgery, James Syme. Over three years, Syme performed over 1,000 surgeries.

- Lister quickly became Syme’s right-hand man, taking on more responsibility at Edinburgh’s Royal Infirmary and assisting him with complex surgeries.

- While working as an assistant surgeon at the Royal Infirmary, Lister gained the respect and adoration of those who worked with him.

A lucrative, illegal trade supplied fresh corpses to anatomy schools. There weren’t enough legally donated bodies to keep up with the burgeoning number of medical schools. So, body snatchers crawled around the city, exhuming and selling corpses. Without the thousands of corpses procured for anatomists, Edinburgh would not have established its global reputation for trailblazing surgery.

- Patients continued to die of infections at the Royal Infirmary, and Lister began examining his patients’ tissue samples under his microscope in an attempt to better understand what happened at a cellular level.

- He recognized that excessive inflammation often preceded sepsis, and then the patient would develop a fever.

- What connected inflammation and hospital gangrene? Why did some inflamed wounds become septic while others didn’t?

- There was no consensus about why infections happened. Some believed it was from poison in the air, but no one knew the nature of that poison.

- He especially wanted to pinpoint the role that the central nervous system played in inflammation.

- He vivisected a large frog and removed its entire brain.

- Vivisection, the act of cutting into living animals for scientific investigation, has a long history. Lister saw it as a necessary evil of his profession.

- He discovered that inflammation from an incision or a fracture was part of the body’s natural healing process, which was a groundbreaking realization.

- He recognized that excessive inflammation often preceded sepsis, and then the patient would develop a fever.

University of Glasgow – 1859

- He was appointed Professor of Clinical Surgery at the University of Glasgow.

Glasgow suffered a large amount of filth, crime, and disease. And, its intellectual atmosphere was very different from the one in Edinburgh—the Glasgow medical community was more authoritarian and didn’t welcome innovation readily.

- Later, he was put in charge of patients at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

- The surgical wing was one of the most unsanitary places he ever worked.

- Lister, true to his Quaker roots, exhibited an unusual level of compassion, refusing to use the word “case” and insisting that each patient be treated with the same care and regard afforded to the Prince of Wales.

- He discovered that blood remained partially fluid for several hours in a rubber tube, but clotted immediately if placed in an ordinary cup.

- He concluded that blood coagulation was caused by the influence exerted upon it by ordinary matter; the contact was very brief but nonetheless caused the blood to change, which induced a mutual reaction between its solid and fluid constituents.

Louis Pasteur

- One of Lister’s colleagues told him about the latest research on fermentation and putrefaction by Louis Pasteur, a French microbiologist and chemist.

- Lister read Pasteur’s publications about the decomposition of organic material, and replicated the experiments at home.

- Pasteur began the research nine years before when a wine merchant approached him with a problem. He had been manufacturing beetroot wine when he noticed that a large number of his vats turned sour while they fermented. Why?

- The vats that smelled bad were covered in a mysterious film.

- Pasteur took samples from each vat and examined them under his microscope.

- He discovered that the shape of the yeast differed depending on the sample.

- If the wine was unspoiled, the yeast was round.

- If the wine was spoiled, the yeast was elongated and appeared alongside rod-shaped structures: bacteria.

- He also realized that hydrogen attached itself to the nitrates in the beetroot, producing lactic acid—thus the odor and sour taste in the spoiled wine.

- He discovered that the shape of the yeast differed depending on the sample.

- Pasteur boldly claimed that yeast acted on the beetroot juice because it was a living organism; this went against the tenets of mainstream chemistry.

- Lister focused on the parts of Pasteur’s research that confirmed what he already believed: Microbial life was the source of hospital infection.

- He realized that he couldn’t prevent a wound from contacting germs in the atmosphere. So, he tried to destroy the microorganisms within the wound. The best method would be by antiseptics (as opposed to heat or filtration).

- In 1865, he started testing antiseptics and chose carbolic acid.

- He limited his trials of carbolic acid to compound fractures, where splintered bone lacerated the skin. This kind of break had a high rate of infection and often resulted in amputation.

- A few months later, an 11-year-old’s leg was run over by a cart, and he had been exposed for hours on the street.

- Lister washed the wound thoroughly with carbolic acid. After the surgery, the wound healed cleanly.

- Lister developed a technique for disinfecting the skin around an incision with carbolic acid and then dressing the cavity.

- Not a single instance of infectious disease occurred on Lister’s wards once he introduced his system.

- In 1869, Lister was elected to the Chair of Clinical Surgery at the University of Edinburgh.

Dissent

- Although older surgeons tried his antiseptic treatment, they struggled to accept germ theory, which was at the heart of his system. If surgeons misunderstood the cause of infection, they were unlikely to apply his treatment correctly.

- It was difficult for many at the height of their careers to accept that for the past 20 years they inadvertently killed patients via infected wounds.

- Slowly, surgeons around Europe employed his methods.

- His followers, who later became known as the Listerians, soon dominated the British medical community, and spread the doctrine of antisepsis.

America – 1876

- Lister spoke at the International Medical Congress in Philadelphia, where very few accepted germ theory.

- A minority of American surgeons had adopted Lister’s antiseptic system.

America had recently endured a civil war that claimed tens of thousands of lives due to appalling battle injuries and infection. Army surgeons often used cold, damp earth to pack open wounds.

- Lister’s speech was not well-received (one attendee accused him of being mentally unhinged).

- Nonetheless, he criss-crossed the country, stopping in several cities to lecture to medical students and surgeons about antisepsis.

- Those who tried his system reported positive results.

- Soon after, Massachusetts General became the first American hospital to require the use of carbolic acid as a surgical antiseptic.

Lister’s legacies

- Other than saving millions of lives through his discoveries and persistence, Lister influenced surgeons to be more proactive when it came to postoperative infection.

- A preoccupation with cleanliness sprang forth, and a new generation of carbolic acid cleaning and hygiene products flooded the market.

- Dr. Joseph Joshua Lawrence attended Lister’s lecture in Philadelphia; in 1879, he manufactured his own antiseptic and called it Listerine.

- Jordan Lambert began marketing it to dentists as an oral antiseptic.

- Dr. Joseph Joshua Lawrence attended Lister’s lecture in Philadelphia; in 1879, he manufactured his own antiseptic and called it Listerine.

- Robert Wood Johnson also attended Lister’s Philadelphia lecture.

- Inspired, he and his two brothers founded a company to manufacture the first sterile surgical dressings and sutures mass-produced according to Lister’s methods. They named it Johnson & Johnson.

- One of his students argued that without Lister, hospitals might have ceased to exist because large hospitals were being abandoned due to high rates of infection.

And More, Including:

- Details about famous surgeon Robert Liston and the miraculous use of ether as anesthesia in 1846

- (Unfortunately, with newfound confidence about operating without inflicting pain, surgeons became more willing to operate and incidences of postoperative infection increased)

- The fierce debate between contagionists and anti-contagionists: How did infection spread?

- Lister’s intensely close relationships with his father, the rest of his family, and James Syme, all of whom gave him strength and hope

- The throngs of dissent that Lister faced in spite of his incredible successes, especially regarding the use of carbolic acid

- Lister’s ingenious discovery of using catgut for ligatures

- How Lister’s ad hoc abscess drain invention saved Queen Victoria’s life

- Lister successfully performing his first mastectomy using carbolic acid, which brought new hope for the future of breast surgery

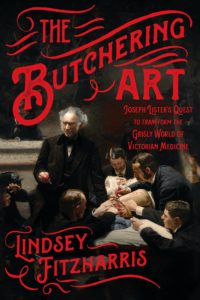

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine

Author: Lindsey Fitzharris

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Pages: 304 | 2017

Purchase

[If you purchase anything from Bookshop via this link, I get a small percentage at no cost to you.]