The Non-fiction Feature

This week’s compelling non-fiction book

Also in this Weekly Bulletin:

The Fiction Spot: A Manual for Cleaning Women by Lucia Berlin

The Product Spot: Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library

The Pithy Take & Who Benefits

The current government safety net assumes that families have access to full-time, stable employment at a living wage, even though the low-wage labor market fails to deliver. For the unemployed, even those with children, there is effectively no cash assistance—not even to weather temporary setbacks—and as a result, parts of society suffer enormously and needlessly. Authors Kathryn J. Edin, a sociology and public affairs professor at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School, and H. Luke Shaefer, the director of Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan, write about 8 families with children who had spent at least 3 months living on a cash income of less than $2/day/person.

Edin and Shaefer’s extensive and thorough research demonstrates that most people living under $2/day/person have had strokes of bad luck that unravel everything and, despite good work habits and unrelenting motivation, they are unable to work, to the extreme detriment of their children.

Edin and Shaefer hope for better through innovative methods that reward working families, unattached to the stigma of traditional welfare. This book is for people who seek to understand: (1) why the number of virtually cashless families has increased this millenia; (2) how these families scrape by and how they don’t; and (3) the dangers and indignities of low-wage work.

Preliminaries

- The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), a survey of interviews with tens of thousands of households each year administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, reveals that the number of the cashless poor has increased.

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (the program provides nutrition benefits to aid the food budget of low-income families) records show a spike in the number of families reporting no other form of income except for SNAP.

- The World Bank’s metrics for global poverty is $2/day/person. In America, “deep poverty” is considered to be $8.30/day/person.

- In 2011, 1.5 million households (roughly 3 million children) were at $2/day/person—one out of every 25 families with children in America.

- More than ⅓ of the families were headed by a married couple.

- A system of tax credits for the working poor has expanded, especially the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which is a refundable tax credit that either lowers the amount of federal tax owed or returns money at tax time.

- If the amount for which a low-income worker is eligible is more than what is owed in taxes, they get a refund for the difference.

- EITC is considered pro-work, so it’s politically popular.

The Outline

A Brief History of Welfare

- After the Civil War, there were many widowed mothers, and states provided mother’s aid programs. During the Great Depression, money ran out. Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) was created, based on the assumption that it was best for a widowed mother to raise her children at home.

- This program expanded to 3.6 million people by 1962.

- President Lyndon Johnson declared a war on poverty.

- But, between 1964 and 1976, the number of people receiving cash assistance ballooned from 4.2 million to 11.3 million even though the President did not expand eligibility.

- As costs increased, AFDC’s unpopularity grew. But, the largest, most representative survey of American attitudes showed that nearly 70% of the American public believed that the government spent too little to assist the poor.

- In 1976, Ronald Reagan campaigned nationally to reform welfare.

- His campaign speeches featured a “welfare queen” who duped the government. The emphasis on race became widespread and virulent: she was black, decked in furs, etc.

- Although a disproportionate percentage of blacks participated in AFDC, they were not the majority of recipients, who were white.

- By 1988, there were 10.9 million recipients on AFDC, about the same number as when Reagan took office. Four years later, when President George H. W. Bush left office, there were 13.8 million.

- His campaign speeches featured a “welfare queen” who duped the government. The emphasis on race became widespread and virulent: she was black, decked in furs, etc.

- In the early 1980s, Harvard professor David Ellwood produced the first reliable estimates of how long the typical welfare recipient stayed on welfare: roughly 2 years.

- He defended welfare as a temporary hand up, and was shocked by the ensuing vitriol (he received many angry letters and phone calls). He realized that Americans didn’t hate the poor as much as they hated welfare.

- Thus, he thought that a good anti-poverty policy would render help while requiring work.

- Ellwood had many ideas to fix welfare, such as providing high-quality education and training opportunities, but his ideas about imposing time limits and work requirements received the most attention.

- He defended welfare as a temporary hand up, and was shocked by the ensuing vitriol (he received many angry letters and phone calls). He realized that Americans didn’t hate the poor as much as they hated welfare.

- In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed welfare reform, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), into law.

- Adults receiving cash assistance could stay on the program for two years without any work requirement. After that, they had to work.

- All federal welfare funds would be passed to the states in block grants, allowing states greater latitude in how they spent the money.

- This essentially capped funding for the program, so a state didn’t have to provide assistance if the cost exceeded its allotment.

- States must impose a five-year lifetime benefit cap for cash assistance using federal funds, but they can impose shorter time limits.

- No one with children would have the legal right to receive welfare from the government, even if there is no other means of support.

- At the peak of the old welfare program in 1994, it served more than 14.2 million people (including 9.6 million children). In fall 2014, TANF was only serving 3.8 million people, and was lifting only 300,000 households with children above the $2/day/person mark.

- There were successes: In 1993, 58% of low-income single mothers were employed, and by 2000, nearly 75% were employed. Child poverty rates and the national unemployment rate dropped.

- But, among those who found work, the wages, benefits, and overall quality of their jobs were low. As a result, poverty among “welfare leavers” remained high.

- As the authors demonstrate, many people eligible for TANF either don’t know about it, or are deterred by long lines and bureaucracy.

- By 2014, 1.4 million families on SNAP had no other income.

- There were higher rates of family homelessness, as tracked by schools: in 2005, 656,000 such children and in 2014, 1.3 million.

- The rise of American households with children living on $2/day/person is clearly linked to the dissipation of the cash assistance system, which no longer provides support during emergencies.

Work Dilemmas

- Most of the families that live under $2/day/person circumstances are workers that can’t find or keep a job. Roughly 70% of children who experienced $2/day/person in 2012 lived with an adult who held a job at some point during the year.

- Yet even when working full-time, these jobs usually do not lift a family above the poverty line.

One interviewee, Jennifer, was working full-time at $8.75 an hour and had a temporary housing subsidy, but still struggled to pay for rent, utilities, food, a bus pass, and winter clothes for her kids. Jennifer had been a good cashier, sandwich maker, waitress, custodian, but this didn’t protect her family from stays in homeless shelters.

- A quarter of the jobs in America pay too little to lift a family of four out of poverty.

- Some might point to the personal failings of the people who hold or held those jobs.

- But this ignores the actions of employers that adopt policies that ensure regular turnover, which cut costs that come with a more stable job, including guaranteed hours, benefits, raises, etc. The jobs themselves set workers up for failure.

- This is why wide scheduling availability, essentially 24/7, is crucial for getting and keeping a low-wage job.

- But, this means a patchwork of unreliable child care arrangements.

- American workers lose billions of dollars each year to “wage theft,” which are violations of labor standards, such as paying less than the minimum wage, forcing employees to work off the clock, and not paying overtime rates.

- Although SNAP increases as wages decrease, it is an unreliable form of immediate aid, especially with an unstable job. Each fluctuation in paycheck must be reported to the Department of Human Services (DHS), but if hours sink to zero, it might take DHS a month to adjust benefits upward, and a family would go hungry that month.

- For homeless people, communication poses an issue. If a job applicant lives at a homeless shelter, there’s one phone number, the secretary has to go find them, possibly leave a note, etc., during which time the interviewer might have moved on.

- The 1996 welfare reform didn’t improve the conditions of low-wage jobs.

- Moving millions of unskilled single mothers into the labor force in the mid-1990s may have diminished the quality of low-wage jobs. The pool of available workers increased, and when more people compete for the same jobs, wages usually fall.

Another interviewee, a mother named Madonna, was having difficulty with her apartment: There were huge bugs and the landlord did nothing. Then, her cash drawer at work was short $10 and she was fired even though she had worked there for years. The employer found the $10 afterwards, but she was not asked to return. With no rental income, she and her daughter were evicted and forced to trek from shelter to shelter.

Housing Dilemmas

- Housing costs consume far more of low-wage incomes than is affordable. HUD states that a family that spends more than 30% of its income on housing is cost-burdened.

- There is no state in which a family that is supported by a full-time, minimum-wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent without being cost-burdened.

- Children experiencing $2/day/person are more likely to live with people outside their immediate family, which can lead to sexual, physical, or verbal abuse.

- In 2001, 63% of very low-income households were putting more than half their income toward housing. In 2011, it was 70%.

- Between 1990 and 2013, rents rose faster than inflation.

- Between 2000 and 2012, rents rose by 6%, while the average renter’s income fell 13%.

- The number of extremely low income renters has grown dramatically—up by 2.5 million—while the supply of affordable rentals has remained flat. Thus, many of the poorest cannot compete in the rental market.

- HUD tries to alleviate some of this burden by maintaining public housing, but the waitlist is long. In NYC in 2013, there were 268,000 on the waitlist; public housing is not easily attainable during an emergency.

- If someone tries to live with family, the family usually isn’t much better off because poverty is often generational.

- Poor children are exposed to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect, etc.) at alarmingly high rates, stemming from an unusually high and erratic dependence of living with family and friends.

- Exposure to just one ACE event can negatively affect a child’s life chances.

Three of the parents featured in the book have a child who attempted suicide, and two have daughters who sold their bodies in exchange for food and money.

Survival Strategies

- Using public spaces and private charities

- Public libraries offer warmth, a clean and safe bathroom, and access to a computer to complete a job application.

- Private organizations offer free health clinics, job training programs, educational programs, and shelters (though most shelters won’t let people stay for long).

- Income-generation strategies

- Donating plasma as often as legally possible, collecting aluminium bottles, selling children’s SSNs, and other desperate strategies to create cash.

- Although selling SNAP is rare overall, it is common for those living under $2/day/person—SNAP, though valuable, is simply not as valuable as cash.

- Without cash, activities are restricted. A person can’t buy an outfit from Goodwill to wear to a job interview, or wash clothes, or buy their child winter boots.

- Those trading SNAP for cash might be able to keep utilities on, but doing so virtually guarantees that the family goes hungry. Hunger often puts mothers and children at risk of demeaning and dangerous sexual liaisons. Not having cash basically ensures that people have to violate the law to survive.

- The penalty for selling SNAP is a fine of up to $250,000 and prison term of up to 20 years or both.

How To Integrate the Poor—Particularly the $2/day/person—into Society

- All deserve the opportunity to work.

- Government-subsidized private sector job creation: There was a short-term subsidized jobs program through the TANF emergency fund where TANF dollars were given to employers with incentives to hire unemployed workers.

- This created over 260,000 jobs with an investment of only $1.3 billion.

- Improve the quality of jobs and raise wages: Most economists agree that the minimum wage could be raised to at least $10/hour without driving down the supply of jobs.

- New research shows that workers are more productive with employers who pay higher-than-average wages, rely more heavily on full-time workers, employ stable scheduling practices, and offer more fringe benefits.

- Government-subsidized private sector job creation: There was a short-term subsidized jobs program through the TANF emergency fund where TANF dollars were given to employers with incentives to hire unemployed workers.

- Parents should be able to raise their children in a place of their own.

- Rents have risen and incomes have fallen; thus, it logically follows to increase renters’ incomes.

- Not every parent will be able to work, or work all the time, but a family’s well-being should nonetheless be ensured.

- There should be a temporary cash cushion. Since most families work, a “family crisis account” could be created for families to access a finite number of times over a given period.

- Expand the EITC: It’s tied to employment, the tax credits are included as part of the federal tax refund (the benefit is earned, like a reward for hard work), and people don’t have to go to a welfare office (most of the beneficiaries can conduct business at a place like H&R block).

The families in the book dream of a good-paying job, around $10/hour, with roughly 30 hours of guaranteed work. A set schedule (so they can find care for their children) is a plus. But low-wage employment is perilous: low pay, few hours, unpredictable schedules. The weaker the safety net, the more the informal work, such as selling plasma, will increase.

And More, Including:

- Information about how Edin and Shaefer collaborated to create such thorough surveys

- A thorough chronology of welfare reform from Reagan to Clinton

- The effect of race when applying for jobs, especially low-wage jobs

- A brief history of welfare in Mississippi, and how a lack of charities, public transportation, good healthcare creates a storm for $2/day/person families

- The crucial emotional and physical importance of making these families part of society

- The art of stretching basic resources to make them last

- Details on SNAP and how it benefits families

- Fuller stories about each of the families featured in the book: their struggles, hard work, moments of desperation, bad luck, and abuse

- Suggestions for effective anti-poverty policies

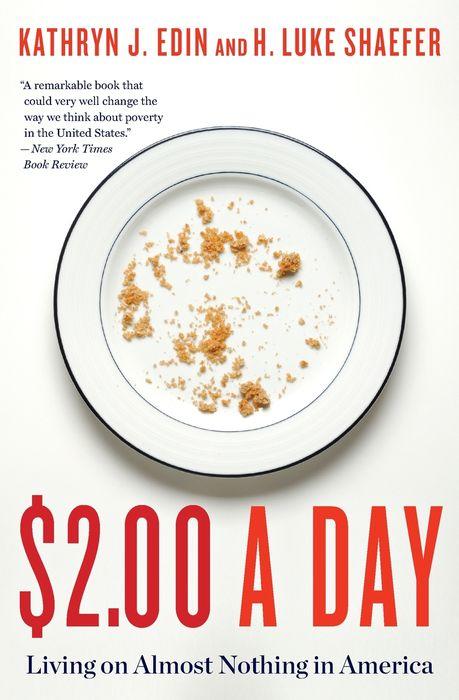

$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

Author: Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Pages: 210 | 2015

Purchase

[If you purchase anything from Bookshop via this link, I get a small percentage at no cost to you.]